We’re advised to write briefly to keep our readers’ attention in this 280-character world. As copyeditors, we’re directed to cut the deadwood. In editing, “deadwood” is a word or phrase that doesn’t add anything to the sentence.

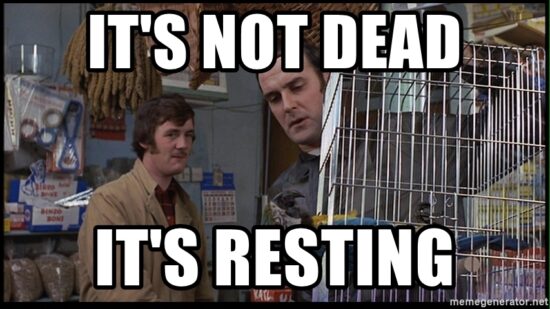

The trick, of course, is telling when something is truly dead and not merely resting.

Take in order to. Is it really deadwood?

Many usage experts think so, declaring the infinitive is fine on its own. Garner’s Modern English Usage notes that the phrase is wordy but useful when there is another infinitive already in the sentence. So while in order should be deleted from “In order to control class sizes, the district will also place seven portable classrooms at the four schools,” it could be kept in “The controversy illustrates how the forces of political correctness pressure government to grow in size and arbitrariness in order to pursue a peculiar compassion mission” because there’s already an infinitive in the sentence.

Yet there’s a flaw in that thinking.

Just because a sentence has more than one infinitive doesn’t mean we have to dress one up, as this sentence from another entry in Garner’s demonstrates: “To be sure, a subtle or complicated thought may need to be clarified by a careful restatement.”

In order doesn’t add a little bit of life to an infinitive. It’s part of an idiom that means “for the purpose of” (The American Heritage Dictionary), and there are plenty of examples in which in order to needs to be right where it is.

Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage points to two examples in particular that would be worse if we deleted in order:

The critic betrays an unconscious admiration … in the sublime images he is driven to in order to express the depths of his exasperation.

John Butt, English Literature in the Mid-Eighteenth Century

I dreamed last night that I had to pass a written examination in order to pass the inspection there.

Robert Frost, letter

Perhaps that explains why we stubbornly keep using in order to: we know that in some instances it has a purpose. A quick check in Google News returned 641 million instances of the phrase. The Corpus of Contemporary American English returned 91,458 instances (1990–2019), and Google Books returned 351 million.

Clearly, we like the phrase.

Don’t reflexively hit the delete key on in order. Stop to decide whether you need just the infinitive or the idiom. Remember the idiom’s meaning, and then ask yourself:

- Does the idiom help avoid awkwardness, such as “driven to … to express” in the example above?

- Does it give the sentence a rhythm it will lose without it?

- Does it emphasize something that needs to be emphasized?

Perhaps your sentence will be better off without in order. But chances are good, that in order to isn’t dead—it’s just resting.

A version of this article first published on Copyediting.com on February 12, 2013.

I may be very old fashioned, but I am inclined to disagree that there is ever a sentence that is worse for deleting “in order to”. In my experience, it generally appears in passages that the writer wants to “elevate” with more “precise” language. While it is almost always wordier than a more active alternative, it also detracts from the point of the sentence. Consider your examples: “The critic betrays an unconscious admiration … in the sublime images he is driven to in order to express the depths of his exasperation.” This could be said: “The critic betrays an unconscious admiration … in the sublime images he compulsively uses to express the depths of his exasperation.” More direct, and free of the passive “driven to”. Likewise “I dreamed last night that I had to pass a written examination in order to pass the inspection there.” Consider “I dreamed last night that I had to pass a written examination before I could pass the inspection there.” Again, more direct, fewer words, all active.

My own preference is for more direct, fewer active words. But that’s a personal choice and not the only acceptable one. Sometimes indirect serves the copy better. Sometimes more words or passive words are better. Absolutes can lock us into awkward, inappropriate, or meaning-changing copy. Editing should serve the writer, the reader, and the copy rather than a set of rigid rules.

I don’t like absolutes either, so perhaps I could have said “I do not recall ever seeing an instance of ‘in order to’ that a careful meaning-preserving edit couldn’t improve.” I don’t have “rigid rules” and I don’t change anything that the author considers necessary–that’s not my job. That doesn’t mean I don’t still think the sentence could be improved, but my job is to point it out, offer an alternative, and accept the author’s preference. I too think of editing like tree pruning – the owner knows how they feel about the tree, and the tree pruner’s job is to point out the problems, potential problems, and possible solutions, and then do only what the owner considers appropriate, which may be nothing.

Thanks for clarifying, Nora! My apologies if it felt like I was shaming you. That was not my intent.