Zombie rules are grammar rules that follow you around like the undead. They’re not really grammar rules, though. Some are stylistic choices, while others are made-up nonsense to make English work more like Latin. In this series, you’ll learn why the rules don’t work and what rule you can follow instead.

Zombie Rule: Don’t Use “Try And.” Use “Try To” Instead.

Does the following sentence from Adweek bother you:

It is tempting—as well as, in liberal circles, heretical—to try and separate Roger Ailes from his politics.

Some language pedants will be immediately drawn to try and and will insist that it should be try to. But should it be? Let’s take a look.

Try And’s History

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and Online Etymology Dictionary both date try and as in “to attempt, to test” to the 14th century. The OED ’s first reference for try and dates to 1686:

They try and express their love to God by their thankfulness to him.

The history of monastical conventions and military institutions (1686)

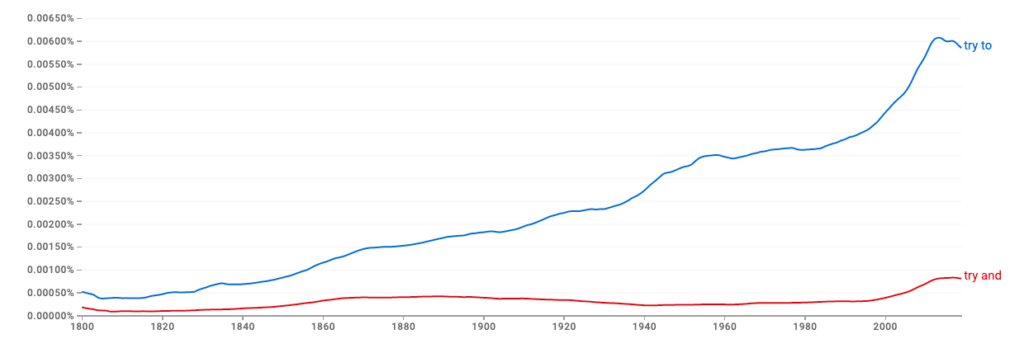

Right away, we can see we’re not dealing with a new concept. Try and has been in common usage for over 300 years. This Google Ngram shows that although try to has been more common than try and, the difference was fairly consistent until the early 19th century.

After 1820, usage of try and remained stable, but that of try to shot way up. According to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of English Usage (MWDEU), try and started to be criticized as ungrammatical at that time. Never mind that by then, the usage had been in circulation for over 100 years and similar constructions (e.g., go and) had been around since the 13th century. Clearly, people started believing it to be ungrammatical, yet try and continued to be used to some extent.

What the Usage Experts Say

By the early 20th century, usage experts were advising that try and was a legitimate, if casual or idiomatic, construction. In 1926, H. W. Fowler wrote in his Dictionary of Modern English Usage that try and “is an idiom that should be not discountenanced, but used when it comes natural.” In 1957, Bergen Evans and Cornelia Evans wrote in A Dictionary of Contemporary American Usage that try and is “standard English.”

While R. W. Burchfield, in The New Fowler’s Modern English Usage (1996), is undecided about try and’s legitimacy, he notes many uses of it in literature. Finally, Bryan Garner notes in his Modern English Usage (5th ed.) that try and is a casualism in American English and a standard idiom in British English.

What We Really Say

The experts can tell us to use one construction over another all they want. The question is whether we listen.

| Source | try and | try to |

| Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) | 23,050 | 148,651 |

| Time magazine | 243 | 8,549 |

| Google Books (21st century) | 11.6 million | 61.4 million |

| iWeb (2017) | 390,944 | 1.7 million |

| 499 million | 2.5 billion |

All results from the above table are from written modern texts (spoken texts were filtered out of COCA), and all but the iWeb and Google results are from edited texts. Clearly we are still using try and, but we continue to use try to more often. Surprisingly, the gap between the two is smallest within Google News results. Although newspapers tend to written less formally to appeal to a mass audience, Google results contain many, many URLs that have not been written by professional writers, let alone edited. But the results seem to indicate that we use try to in our most formal writing, and try and is very common in less formal situations, which backs up what Garner and MWDEU tell us.

Zombie Rewrite

Try and is acceptable in less formal writing and speech in American English. Try to is preferred in more formal contexts.

A version of this article originally published on October 6, 2011.